Of Radicals and Revolutions

In English I'm a painfully slow reader. My mind wanders all the time, and I have to backtrack to wherever I was before I drifted away, hoping I won't meander down the same side paths on the second pass. But that doesn't begin to compare with how slowly I've made my way through the kanji in Professor Kyle Ikeda's lecture, which I've blogged about for the last two weeks! At the very least, I'd like to finish one PowerPoint slide on this go round!

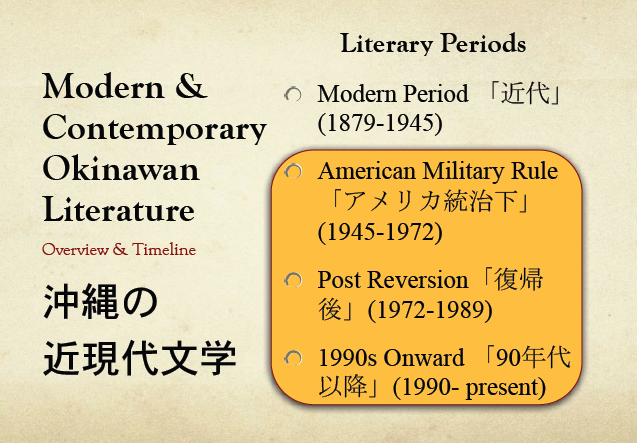

Here again is the slide I began examining last week:

We covered the American Military Rule section, which brings us to this bit:

復帰後 (ふっきご: post-reversion)

This word lies at its root:

復帰 (ふっき: return; comeback; reinstatement) to revert + return

I'm intrigued that 復帰後 contains two instances of 彳, the "going person" radical. That's probably coincidental, but let's see what Henshall's etymologies reveal:

復 (782: to return to, recovery)

The radical means "to go" here. So 復 breaks down as "to go" + "go back." The idea is "to go somewhere and then reverse (one's steps)."

後 (111: behind; after)

The radical means "road, movement" here. But the whole of 後 means "to make (abnormally) little progress" (which hits close to home!). That meaning indicates "delay" and by extension "coming after" or "behind."

So 彳sets us in motion both times, but only 復 has any velocity, and that kanji sends us backward!

Despite this prominent theme of lollygagging and the way it makes me feel inert, I will force myself to press on to the next word:

以降 (いこう: on and after; as from; hereafter; thereafter; since)

to the ... + onward, afterward

I associate 降 with falling precipitation, and Halpern says that this kanji primarily means "to descend." But in a funny little corner of its existence, it also means "onward, afterward." The only example he provides for that is 以降.

Speaking of descending, we've worked our way to the bottom of that slide! Hooray! Now for the next one that caught my eye:

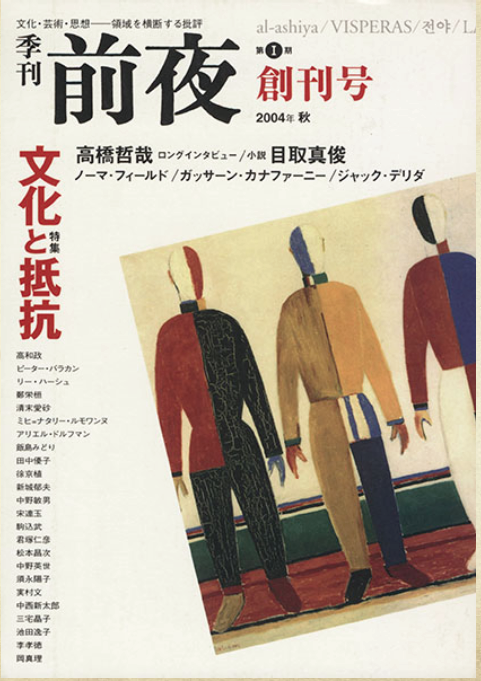

This is the Autumn 2004 cover of the magazine 「前夜」, pronounced ぜんや and translated as "right before something important happens.” The word 前夜 goes quite well with 革命 (かくめい: revolution)—that is, 革命前夜 means "the eve of the revolution" or "right before the revolution"—so Japanese people associate the title with revolution, according to my proofreader.

I find the graphic oddly compelling. And of course my eye also goes to some of the kanji, including this horizontal red word:

創刊号 (そうかんごう: first issue) launching a publication (1st 2 kanji) + number

Here's the word at its root:

創刊 (そうかん: launching a publication (e.g., a newspaper or magazine))

to initiate, originate, start + to publish

I see two swords! Each kanji "wears" a 刂 (a variant of the "sword" radical 刀) on its right side.

Henshall breaks down 創 (to initiate, originate, start) as "wounded" (倉) + "sword." That sounds like it could herald the end of someone's life, but he says "start" is one meaning (albeit a borrowed one)!

With 刊 (to publish), the 干 acts phonetically to express "carve, engrave" and "cut," says Henshall. The whole of 刊 originally meant "to engrave" but came to be associated with engraving as part of printing. It later acquired the definition "to publish."

In 創刊 as a whole, the pen seems to be mightier than the sword!

Of course, writing can spark just as many conflicts as a swordfight. In saying that the 創 in 創刊 means "to initiate, originate, start," I drew on Halpern's analysis. My proofreader disagrees, breaking down 創刊 as creation + publication.

In other words, he opposes Halpern, which conveniently brings us to this vertical red word on the journal cover:

抵抗 (ていこう: resistance; opposition; standing up to) to resist + to resist

Why are there so many "hands" in this word? I'm talking about the 扌 component on the left of each kanji. That's the variant form of 手, the "hand" radical. Here's Henshall's take on each character:

抵 (1612: to resist)

The "hand" radical combines with 氏 (typically "bottom of hill"), which acts phonetically here to express "push back (with equal force)." Together, the two sides originally meant "to push back with the hand," which evolved to mean "resist" and "match" or "prove equal."

抗 (1246: to resist)

The "hand" radical joins the bit on the right (usually "high, straight"), which acts phonetically here to express "block" and "obstacle" or "obstruct." If you "block with the hand," you "resist" and "protest."

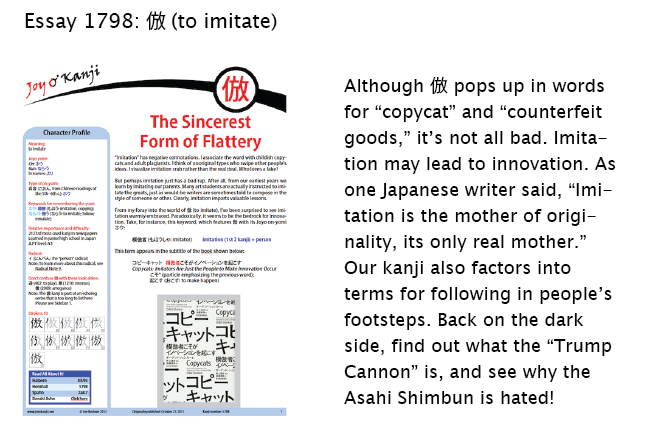

I will resist continuing, except to offer you a preview of the newest essay:

Have a great weekend!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments