In the Woods of Memory

I'm late again. To my chagrin, I've become the sort of person who starts every email with apologies for slow replies. That habit is now seeping into my blogs, as well. Oh, well. Perhaps the frequent apologizing is making me that much more Japanese in spirit!

My constant excuse these days is that I'm overextended, spread so thin that I'm quite possibly developing holes! My excuse for this particular weekend is actually related to Japan. I attended a lecture on Okinawa—specifically on the trauma people experienced during the Battle of Okinawa (during World War II) and how that trauma has filtered down through the generations. The speaker, Dr. Kyle Ikeda of the University of Vermont, based his talk on these two books:

1. Okinawan War Memory: Transgenerational Trauma and the Fiction of Medoruma Shun, which Ikeda published in 2014.

2. In the Woods of Memory, a novel by Okinawan author Shun Medoruma. Newly translated into English by Takumi Sminkey with an afterword by Ikeda, the book has just been published by Stone Bridge Press. That press also published my Crazy for Kanji. I follow Stone Bridge closely, which is how I learned about the event.

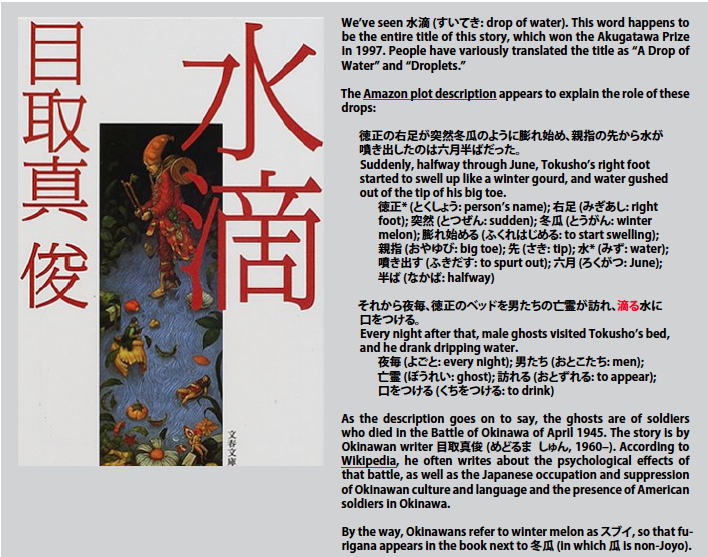

Kanji drew me there, in part. I found out about Medoruma two years ago in writing essay 1626 on 滴 (drop (of liquid)). Here's my caption about his short story「水滴」:

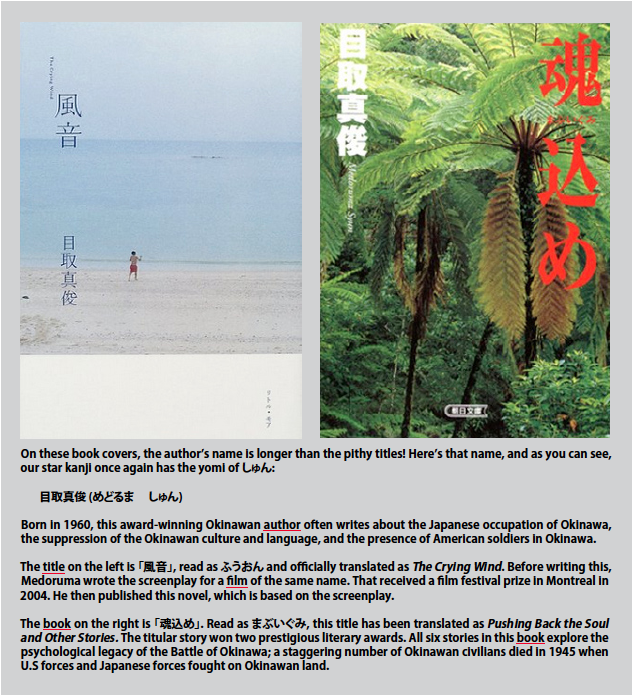

Three months later, I came across Medoruma again in writing essay 1371 on 俊 (excellent; genius; talented person), as that's the kanji for the author's given name. This is what I wrote there:

Ah, here's a bit of synchronicity. I see this in Ikeda's biography:

His translation of Medoruma’s “Mabuigumi” (Spirit Stuffing) appears in the literary journal Fiction International (2007), and in Living Spirit: Literature and Resurgence in Okinawa (2011).

This weekend's event was held in a new building with abundant glass and wood, a building that belongs to J-Sei, an organization for elderly people of Japanese descent. All the signs on the doors are bilingual, so I had a great time walking around, seeing what I could decipher and what was new to me.

Similarly, Ikeda made his PowerPoint slides bilingual, which added an extra level of stimulation for me, as well as frustration. Over and over I wanted to pull out my phone and take photos of the slides so I could present my kanji findings to you. But I couldn't think of anything much ruder than occasionally blinding the speaker with a flash and possibly having my phone go off with various notifications. So I disciplined myself to let the kanji flow by, unrecorded and lost to posterity! (Well, lost to me, I should say. I'm quite sure Ikeda still has the presentation in his computer!)

Ikeda did touch on one topic that wasn't hard to remember. Medoruma published his novel with this title:

「眼の奥の森」

眼 (め: eye); 奥 (おく: inside); 森 (もり: woods)

The translated book mentions the original title and provides the yomi I've presented above.

The first kanji jumps out at me. I'm most familiar with it from 眼鏡 (めがね or がんきょう: glasses). Although 眼 (640: eye; insight) carries three Joyo readings—namely, ガン, ゲン, and まなこ—the list doesn't not include め. That is a non-Joyo kun-yomi, one that surfaces when people read 眼鏡 as めがね, which they typically do, even though it's ateji.

Let's return to the strange title 「眼の奥の森」. It literally translates as The Woods in the Back of the Eye!

Why did the author not choose 目 (め), the more common way of representing "eye," if he wanted that meaning and yomi? I imagine that that Medoruma liked the second major meaning of 眼, "insight." After all, 眼 appears in words such as these:

眼力 (がんりき: insight, power of observation)

眼識 (がんしき: insight)

Even 眼鏡 as めがね (but not as がんきょう) can mean "judgment, insight." So the choice of 眼 prompts readers to think about insights, not eyeballs.

I checked with my proofreader about these ideas, and he agrees that 目 somehow has the nuance of the anatomical eye, rather than the ability to judge. But, he says, that’s not always the case. Take these phrases, for example:

目が利く (めがきく: lit. “eyes are efficient”) means “to have a good eye for something" or "to be a good judge of something”

目が高い (めがたかい: lit. “to have high eyes”) means “to have an expert eye for something”

Both expressions are about the ability to judge correctly.

As for reading the 眼 of the title as め, he says that even though it's non-Joyo, that yomi is fairly common. By contrast, it's rare to read 眼 with the Joyo kun-yomi まなこ! He can think of only two expressions that require that reading:

寝ぼけ眼 (ねぼけまなこ: sleepy eyes; drowsy look)

血眼 (ちまなこ: bloodshot eyes), which figuratively means "frantically looking for something"

Ikeda noted that 眼の奥 points to the interior of the mind, the place where memory resides (if my memory is not failing me here!).

My proofreader responds to that comment with these thoughts: "This is just my guess, but strongly having something in one’s memory connects to the idea of being able to see it even with one’s eyes shut. That may feel like seeing with the back of one’s eyeballs. A nearly synonymous expression is 瞼に浮かぶ (まぶたにうかぶ: to come up on (the back of) the eyelids). The idea is that one can see or remember something even with one’s eyes shut, as if the thing were on the back of one’s eyelids." By the way, 瞼 (eyelid) is non-Joyo.

And what does it mean to have a 森 growing in the mind? I have no idea, except that a forest represents the terror of becoming lost. Perhaps the true meaning will become clear to me once I actually read the book! Speculating on a work of which I know little is dangerous. I think I'd be better off out of the woods!

Have a great week. Oh, and don't forget to check out the newest essay. Here's a sneak preview:

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments