Using One's Noodle

I thought I knew a lot about noodles until I wrote essay 2118 on 麺 (noodles), which certainly made me use my noodle. (Groan!) Below you'll find a sampling of things I noodled over while working on that essay. (Double groan! But at least I haven't worked in a canoodling pun ... yet ... so all should be forgiven. Right? Right?!)

East Doesn't Meet West

Westerners largely associate noodles with tomato-based sauces and cheese, not with soups. By contrast, the Japanese are likely to submerge noodles in a broth and to slurp them up from there. I had never thought about that difference before.

Pho Goodness Sake!

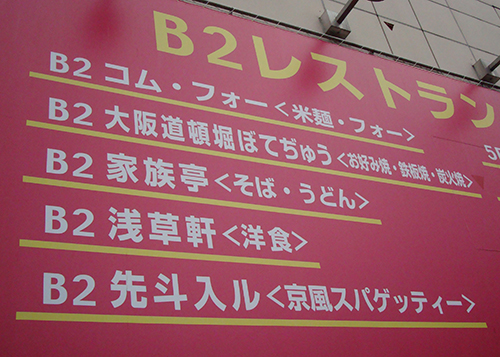

The first white line of this sign looks so simple, and yet it stumped me:

Photo Credit: Kevin Hamilton

Here again is what the line says:

コム•フォー<米麺•フォー>

The kanji part, 米麺 (こめめん: rice noodles), is easy enough to understand, but the rest?

As I discovered, フォー means "pho"! A Vietnamese soup with rice noodles and thin slices of beef or chicken, pho is really common where I live, and now that someone has interpreted the sign for me, it all seems so obvious.

One Vietnamese word for “cooked rice” is com, ignoring tones, so コム likely represents that idea.

As to why the syntax seems repetitive, translating as "cooked rice—pho (rice noodles—pho)," my proofreader explains that this is for the benefit of Japanese readers, most of whom don't know the language or food of Vietnam. The sign starts with the approximate pronunciations of the Vietnamese terms com and pho, then presents the same information in a way that should be more meaningful to Japanese people—namely, "a rice noodle dish called pho."

Shouldering the Burden of Knowledge

If I went to the trouble and expense of creating this beautiful sign, I would make sure it contained no errors:

Photo Credit: Lutlam

Apparently quality control was suboptimal because the first word on the right should be as follows:

担々麺 (タンタンめん or タンタンメン: dandan noodles)

to shoulder + to shoulder + noodles

That is, the 担 should include the "hand" radical 扌, not the "earth" radical 土.

The non-Joyo 坦 means "level," which makes no sense in this context. Of course, it's not intuitive that 担 (to shoulder) belongs in the name of a dish consisting of a spicy sauce and, usually, preserved vegetables, minced pork, and scallions over noodles. However, as Wikipedia explains, vendors in China used to peddle this dish with poles over their shoulders. A basket filled with noodles and sauce hung from each end of the pole, known as a dan dan.

By the way, the other words on the sign are 餃子 (ぎょうざ: gyoza), where 餃 is non-Joyo, and the restaurant name 永吉 (えいきち), which one could interpret as "good luck" (吉) "forever" (永). One way to ensure eternal good luck is to proofread before creating a sign!

Ah, it turns out that this Chinese restaurant was named after the legendary rock singer Eikichi Yazawa (矢沢 永吉). The owner is a big fan.

Edible Game Pieces

Here's a Quick Quiz for you about the following type of noodle:

きしめん (きし麺 or 棊子麺 or 碁子麺: noodles made in flat strips)

In the second kanji rendering, the non-Joyo 棊 is a variant of 棋, meaning “Go” or “shogi.” Both 棋子 (きし) and the 碁子 (usually read as ごし) in the last version mean “stones used to play Go.” Why would anyone name noodles after the board game Go? Choose one option:

a. It's the ideal snack to have while playing Go.

b. The loser of each game has to make noodles for the winner.

c. Originally, きしめん referred to disks of dough resembling Go stones.

d. Go originated as a competition between noodle makers.

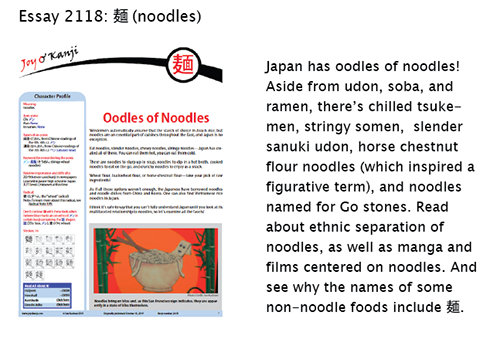

I'll block the answer with a preview of essay 2118:

c. The term きしめん originally referred to a dish made by using the end of a bamboo tube as a “cookie cutter” to produce flat disks of dough. That is, they resembled Go stones. Now, though, きしめん tend to be flat and long.

The Usual and the Ordinary

It's good that you know about きし麺 because that word shows up in the second of these sentences, both of which come from essay 2118:

麺は普通小麦粉から作られる。

Noodles are usually made from wheat.

普通* (ふつう: usually); 小麦粉* (こむぎこ: wheat flour);

作る (つくる: to make, shown here in its passive voice)

そばはそば粉から、うどんやきし麺は普通の小麦粉からできてるの。

Soba is made from buckwheat flour, and udon and kishimen are made from ordinary wheat flour.

そば粉 (そばこ: buckwheat flour); できる (to be made)

Considering these sentences together made me think that the の trailing after 普通 in the latter sentence might be optional. However, that の affects the meaning of the sentence. To understand the syntax better, consider these sentences:

Xは普通の小麦粉からできている。

X is made from ordinary flour.

Xは普通、小麦粉からできている。

X is usually made from flour.

The 普通の works as an adjective that means “ordinary,” whereas the second 普通 serves as an adverb that means “usually.” Moreover, the Japanese comma following 普通 is important. It’s there to clarify that 普通小麦粉 isn’t a single term.

English Etymology

With all that resolved, there's only one matter left to consider—namely, how canoodling relates to noodles, if at all.

To my surprise, there's an etymological connection! The Random House dictionary diffidently suggests that "canoodle" might be the union of "caress" + "noodle." Caressing noodles?! Ah, if I understand the dictionary's system (and I might not), "noodle" in this sense means "fool" or "simpleton." That's certainly not something I encountered in my study of 麺. Perhaps Japanese noodles are smarter.

Be sure to check out essay 2118 if you love noodles—and who doesn't?!

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments