The Spirit of the Thing

I told you last week that I had an uplifting talk with Len Brackett. A hero of mine, he lived in Japan for seven years, learning the fine art of temple carpentry. He now builds Japanese-style houses in California, infusing them with all that he learned as an apprentice in Kyoto.

"Yes, yes," you're thinking. "I already read that blog!"

Hold your horses! What I didn't tell you is that as the conversation progressed, Brackett and I ended up talking about waterfalls. In doing so, he gave the best explanation of Japanese religion that I've ever heard.

As he told me, one of the most wonderful things about Japan is that, in the Japanese mind, "Everything lives somehow. The Japanese don't seem to see a dichotomy between animate and inanimate. The things we think of as inanimate, the Japanese see as animated in some way. When they see a beautiful waterfall or a beautiful rock, their impulse is to make a little house for the spirit that lives in it." He's talking here about a small Shinto shrine, known as a ほこら, which you can write with the non-Joyo kanji 祠.

By building such a shrine in a loving, spontaneous way, people spread their appreciation of the waterfall, rock, or whatever the natural object happens to be. Brackett explains, "Someone else sees the shrine and says, 'Oh, yes, this place is alive. It's really alive.'"

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Kegon Falls in the town of Nikko, which is in Tochigi Prefecture.

"Ultimately, I think that's very, very sane," says Brackett. "It's certainly very charming." He notes that Native Americans similarly think that waterfalls and mountains live.

Brackett has seen the Japanese respond this way not only to nature but also to objects such as a tea bowl. During a tea ceremony, people will handle the bowl reverently, as if it has a spirit.

"Sometimes they'll take that spirit for a walk, as in a matsuri," he says. In kanji terms, he means a 祭り (まつり: festival). In cultural terms, he's referring to the way people parade something of spiritual significance—even a heavy log—through the streets, celebrating its existence.

When Brackett asks the Japanese about Shinto, he receives only foggy replies, if any. As he has come to understand, "Shinto is hard to define. It's a feeling, more than anything else. It isn't all consigned to dogma." In this way, Shinto couldn't be more unlike other religions. "We want rules, and we want to make definitive statements," says Brackett. "The Japanese shy away from definitive statements. They like to leave things open."

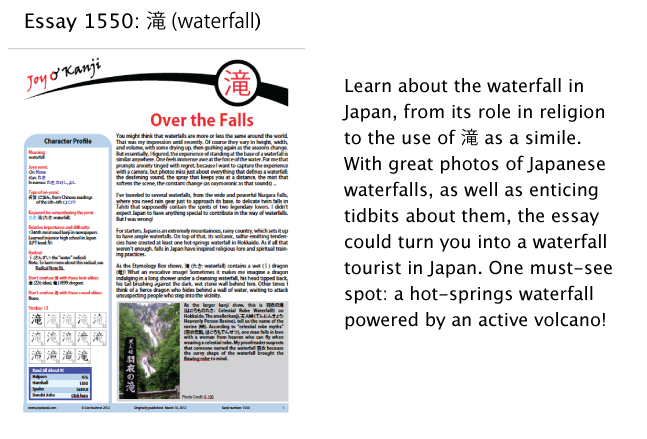

I have just published essay 1550 on the waterfall kanji, 滝. And as it happens, this piece explores the link between waterfalls and Japanese religious beliefs. For instance, in order to attain spiritual and mental purity, some people take painful showers under waterfalls. In addition, an impressive waterfall is supposedly the "personification" of the deity Fudo (不動, ふどう). Here are a few more highlights of this essay:

Whenever I've gazed at waterfalls, I've seen nothing but water, foam, and spray. But to some people in Asia, waterfalls contain quite a bit more. After all, from a kanji perspective a waterfall (滝) is a wet (氵) dragon (竜)! Essay 1899 on 竜 shows in detail how the Chinese have traditionally associated water with dragons, so perhaps this should come as no surprise. Still, it always does. Whenever I think about the components of 滝, I imagine Puff the Magic Dragon enjoying an extremely powerful shower, tipping his head back as the grime of the day flows off his body into a deep pool below.

It's not so hard to imagine this dragon. But can I sense the spirit of a waterfall?

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Nikko waterfall.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Nikko waterfall.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Nikko waterfall.

Ever since I spoke with Brackett, I've been musing about the spirit of objects, and as I now realize, I've heard these animist ideas before in several forms.

When I wrote Crazy for Kanji, a Japanese teacher helped with the research, offering a steady supply of rich information. One day we talked about these two verbs:

なおす: to cure (when written as 治す) or to fix (when written as 直す)

なおる: to be cured (when written as 治る) or to be fixed (when written as 直る)

Whereas なおす is transitive, なおる is its intransitive counterpart, but that distinction isn't the interesting one here. Rather, the teacher drew my attention to the relationship between 治 and 直. Because one can write なおす as 治す or 直す, there seems to be a difference between these words. That is, you're supposed to use 治す for healing a person and 直す for repairing a desk. If you write the wrong kanji in these situations, it's considered incorrect. However, as he told me, this division is actually artificial, because the Japanese don't really distinguish between animate and inanimate objects. When you fix a desk, he said, you heal its spirit. In Japanese, then, healing and fixing are a unified idea, and there's truly just one word here: なおす. In China, however, healing and fixing are separate entities, so the Chinese gave these concepts different characters.

I'm at my desk right now, and I'm hard pressed to sense its spirit. But I once heard someone talk about the soul of a lampshade. I was in a Berkeley lighting store, buying specialty light bulbs, when I spotted the cutest floor lamp I'd ever seen. I had never once thought of a lamp as cute, but with a notched bamboo column and a sassy, contoured shade, this lamp undoubtedly was.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

I spontaneously decided to buy it. I suppose I could have just built a shrine to it, but then that lamp wouldn't be in my life today.

Before I paid, I stood with the store owner, admiring the lampshade, and she commented in a thick Korean accent that the shade gave the piece its "soul." Her comment intrigued me. Maybe she meant that the lampshade had lots of personality; that’s how I would have said it. But her English was good, so I felt that her word choice was deliberate. Did it spring from animist beliefs (or whatever the equivalent is when you're talking about a lamp)?

Since then, I've paid special attention whenever I've heard a similar comment.

For instance, a yoga teacher of mine once said that even if a yoga pose is technically perfect, it's worthless if it has no "spirit."

And when I interviewed a paper maker, one who integrates found objects into her artistic paper creations, she said she loves to use canceled stamps. Why not regular ones? Well, of course that would be expensive, but that's not the point! As she explained, canceled stamps have a certain spirit, just as a face with a few lines has more character.

A photographer-friend told me that if he’s not emotionally present during a photo shoot, the pictures reflect it. The camera absolutely captures whatever he’s feeling, he said. Can that be so? After all, we're talking about a machine. Much as a car cruises along while we space out at the wheel, wouldn't a camera function just fine even if the mind checked out? Apparently not.

So what about the spirit in kanji? Which characters emanate the most personality? It's so hard to choose. How can I? I can't. But I can say what moves me in the moment. To do this, I'm scanning several hundred kanji posted on a bulletin board above my desk, searching for the ones that brim over with life. The following three leap out at me:

黙 (モク, だま•る: silent)

A village (里)! A dog (犬)! Flames (灬) coming out of the base, as if this kanji were a rocket poised to blast off into space! There's so much energy when these three pieces come together. And yet this kanji means "silent"! There's nothing silent about a dog, a fire, or most villages! This is quite a character!

床 (ショウ, とこ, ゆか: bed, floor, alcove)

What is it about the shape of this kanji that speaks to me so powerfully? The hemp kanji, 麻, looks quite similar but does little for me. It's the lone tree (木) standing bravely under a roof (广) that tugs at me. And then there's the fact that 床 can mean "alcove," as in 床の間 (とこのま), which means "a recessed space in a traditional Japanese house where people display art or flowers." How can I not feel drawn to a recessed space?!

聴 (チョウ, き•く: to listen carefully)

An ear (耳) and a heart (心)! We find that combination, too, in 恥 (shame), but there's something more here, something that's balanced on the heart, and it somehow looks important.

I responded to these kanji simply for the way they look:

字面 (じづら: appearance of a character)

I haven't presented the true etymologies here, just whatever made me want to know these kanji better.

Of course, characters fully spring to life in compounds, bringing out unexpected qualities in each other and reflecting a particular spirit. Consider this word:

虎落笛 (もがりぶえ: winter wind whistling through a bamboo fence)

Improbably enough, this word contains a tiger (虎)! And what a poetic meaning: "winter wind whistling through a bamboo fence"! Do you feel the spirit of this concoction? How can you not?!

If inanimate objects have spirits, it can work the other way, too. That is, when we're feeling mechanical and dead inside, an object can reanimate us if we connect with it properly, appreciating everything that it has to offer.

Comments