Smoke Signals

My husband, dogs, and I recently traveled south to Montecito, a beach town near Santa Barbara, California. At a Thai restaurant one night, our server chatted with us about the area and then asked why we had come. I mentioned my upcoming birthday, and before I knew it she presented us with free dessert—a dish of coconut ice cream.

I was delighted by the gesture, scared of the calories, and terrified of how the lactose would affect me. Eating dairy would definitely ruin the rest of the evening. But she had given this dessert with great kindness and joy, so I had to eat it politely, didn't I?

I sampled a bit and was astounded at how creamy and flavorful it was. The small chunks of coconut inside came as a wonderful surprise.

When the server stopped by to see how we liked it, I received the best surprise of all—the ice cream was actually made from coconut milk. What a relief! I could devour the rest without fear (except for the calorie thing).

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

Tea at the restaurant came in a cute cup and presented no quandaries whatsoever.

I later told my language partner Kensuke the story, struggling to say that the ice cream contained pieces of real coconut. He put it this way, typing the sentence into the Skype chat window:

ココナッツの実が少し入ってました。

There was coconut in it.

I had no idea how to interpret 実, which could be either 実 (み: fruit) or 実 (じつ: real). One seldom encounters a situation where both “fruit” and “real” would make sense!

In this case, 実 (み: fruit) applies, and for native speakers this would be clear from context, he said.

Here's the sentence again, now with yomi:

ココナッツの実が少し入ってました。

There was coconut in it.

実 (み: fruit); 少し (すこし: a little); 入る (はいる: to be included)

The 少し means that there was a small amount, not that the pieces were small.

Smoke Signals

Kensuke also shed light on a sentence about something that occurred at another meal, this one back at home. As a high school classmate and I enjoyed a four-hour lunch, we were startled when a spiral of black smoke rose from my wooden garden table. Sunlight streaming through the base of his wineglass had ignited the wood! If we had used a magnifying glass (the classic tool), we might have achieved the same thing, though that definitely wasn't the goal.

I wrote about this experience on Facebook, prompting a Japanese man to respond as follows:

太陽光線がそんなに強いところですか? 珍奇な現象ですが他山の石としないといけませんね。

Was the sunlight that strong? It’s a strange phenomenon, but it teaches you something.

太陽光線 (たいようこうせん: sunlight); 強い (つよい: strong); 珍奇 (ちんき: strange); 現象 (げんしょう: phenomenon)

I didn't understand the red keyword and found this in Breen:

他山の石 (たざんのいし: lesson learned from someone's else mistake; object lesson; food for thought; stones from other mountains (can be used to polish one's own gems)) another + mountain + stone

What did stones from other mountains have to do with my story? I asked Kensuke, who found this etymology, which we translated as follows:

「他山の石」は,中国最古の詩集「詩経しきょう」にある故事に由来する言葉です。

The phrase 他山の石 is derived from a legend from the Shijing, China's oldest poetry anthology.

中国 (ちゅうごく: China); 最古 (さいこ: the oldest); 詩集 (ししゅう: poetry anthology); 詩経 (しきょう: Shijing or The Classic of Poetry); 故事 (こじ: legend); 由来 (ゆらい: origin); 言葉 (ことば: word)

「よその山から出た粗悪な石も自分の宝石を磨くのに利用できる」ことから

Even if the stone from another mountain is inferior, you can use that stone to polish your jewel.

よそ (another place); 山 (やま: mountain); 出る (でる: to come out); 粗悪 (そあく: inferior); 石 (いし: stone); 自分* (じぶん: you); 宝石 (ほうせき: jewel); 磨く (みがく: to polish); 利用 (りよう: use)

「他人のつまらぬ言行も自分の人格を育てる助けとなる」という意味で使われてきました。

Other people's disappointing words and actions have also helped you build character.

他人 (たにん: other people); つまらぬ (disappointing); 言行 (げんこう: speech and behavior); 人格 (じんかく: character); 育てる (そだてる: to develop); 助け (たすけ: aid); 意味 (いみ: meaning); 使う (つかう: to use, shown here in the て form of its passive voice)

Even bad things can play a useful role in life. I certainly understand that idea. I'm more stuck on the concept of using a stone to polish a jewel. That must work, but it sounds all wrong.

Back to the original point, was the spiraling smoke a lesson? It proves a physics concept about the convergence of rays, so that must be what my Japanese friend meant.

Or was there a deeper life lesson embedded in the experience? If so, I have no idea what it was. I love decoding things such as kanji, but I'm not well versed in interpreting smoke signals!

The Latest Essay

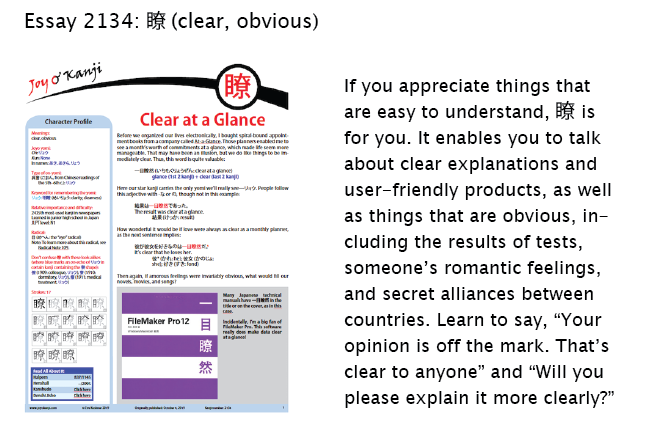

For your reading pleasure, I'm pleased to announce the publication of essay 2134 on 瞭 (clear, obvious). Here's a sneak preview:

If you also find smoke signals opaque, you'll appreciate the way 瞭 instead confers clarity!

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments