Famous for Not Being Good

Long, long ago, I wrote a great deal about architecture, and then that came to a halt and in a sense all I could see was kanji! But a few weeks ago someone asked me to write about architecture, and thanks to our ongoing correspondence I now have buildings on the brain again.

In particular, he made me aware of the freaky Nakagin (中銀, なかぎん) Capsule Tower in the Shimbashi section of Tokyo, and I ended up checking out a few articles about it:

1. Article in English

2. Another article in English

3. Article in Japanese

On top of that brief immersion, I ruminated this week about the following book title from essay 1769 on 雰 (atmosphere), which posts next week:

「日本の名建築をあるく 雰囲気の美学」

A Walking Tour of Noteworthy Buildings in Japan: The Aesthetics of Atmosphere

日本 (にほん: Japan); 名- (めい-: noteworthy); 建築 (けんちく: architecture); あるく (歩く: to walk); 雰囲気 (ふんいき: atmosphere); 美学 (びがく: aesthetics)

I didn't include the cover of that book as art for the essay because the design is drab. Wouldn't you expect a book about architecture to look stylish?!

Anyway, as my proofreader and I went over the possible ways of translating this title, a few points emerged.

I defined 名- as "famous," and he objected that this 名- is closer to “excellent." Because "excellent building" sounded weird to me and because buildings on such a tour would likely be famous, I asked for clarification.

He said, "I prefer 'excellent, noted, great' to 'famous' because famous buildings can be famous for being good or bad." To prove his point, he referred to a collection of crazy famous buildings in Japan.

Ah, back to that!

He then went in a direction I didn't expect at all: "We often jokingly use the unofficial prefix 迷- (めい-) for things or people that aren't very good." As an example, he presented two homophones:

名探偵 (めいたんてい: private detective whose logic is unassailable), such as Hercules Poirot

迷探偵 (めいたんてい: private detective who always guesses wrong)

It's not just a coincidence that 名- and 迷- are homophones. Rather, the Japanese picked 迷- for that very reason—to contrast with 名- while sounding just like it. One could interpret this 迷- as "wandering," but the rendering doesn’t really have anything to do with wandering. It’s just wordplay.

Though the slang term 迷探偵 isn't likely to be in dictionaries, he said, it’s in the title of a detective novel series.

Coming back to the matter of architecture, my proofreader observed that we can use 迷建築 for buildings that are famous for not being good.

Ah, but isn't this extremely confusing in conversation, given that the homophonic 名建築 is high praise for a building?! I suppose confusion is the fun part here!

When I wrote essay 1847 on 銘 (inscription; established name; to engrave on one's mind), I dealt with the close relationship between that kanji and 名. I now see that 名 also has a strong relationship with a most unexpected kanji—namely, 迷.

And here I thought I knew 迷 because I wrote extensively about the term 迷惑 (めいわく: trouble, bother, annoyance) in essay 1942 on 惑 (bewildered; to lead astray). I also blogged about 迷 in reference to the wonderful maze town 迷路のまち (めいろのまち: lit. "Maze Town") on the island of Shodoshima.

But of course it's difficult to know a kanji through and through, as there's always another side to its personality. And that's the ongoing thrill!

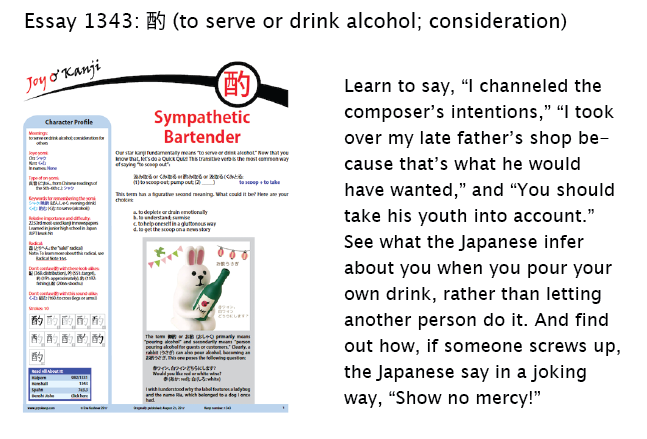

If that makes you long for a drink, 酌 (to serve or drink alcohol) is the kanji for you! Be sure to check out the new essay about it:

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments