Donald Richie: He Covered It All

It was strange timing. For essay 1777 on 塀 (fence; boundary wall; wall), which ran last week, I pulled out three books by Donald Richie, trying to find out how he interpreted Japan's walled-off-ness on a cultural level. I hadn't read any of these books in a long time, but I somehow found the answer immediately.

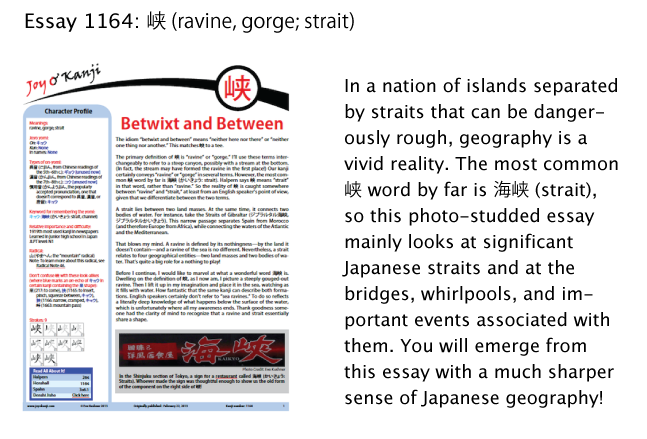

Then for essay 1164 on 峡 (ravine, gorge; strait), which has posted today, I turned to another Richie book, The Inland Sea. Again, I hadn't read it in about a decade, even though it's my favorite book in the world. I knew he said there that the construction of massive bridges across the Inland Sea has destroyed the charms of island life and that one formerly inhabited island was now home only to a pylon. But where had he said these things? I had no idea, so I spent 90 glorious minutes with the book on Sunday, dipping in here and there in the most delicious way. I knew I could have been more efficient about the search, and efficiency is always paramount to me. But I allowed myself the guilty pleasure of spending time with Richie, and I didn't regret it for an instant. How nice to have him back in my life after such a long time!

I had already read the book three times by 2002 when I reviewed it for the Hyde Park Review of Books. I had also pored over the Inland Sea segments that appear in The Donald Richie Reader, which I reviewed back then for three other publications, including Persimmon. I had even seen the documentary version of The Inland Sea. And I've now traveled there twice, feeling deeply fulfilled each time because what I saw on Miyajima and Shodoshima wholly matched the high expectations that Richie created in me with passages such as this: "Houses tumble down the hillsides, fall over each other, and all but end in the water. Their gray-tile roofs almost touch, and small and narrow alleys swarm in all directions. The mud walls, straw showing through, are so close that it would seem the inhabitants move crab-fashion. The port is filled with fishing boats, strange junklike ships with high prows and raked sails, and around them, on the docks, are bales and coils and baskets and boxes. On all sides there is the most glorious confusion" (p. 21).

Though I should have been completely familiar with the book, I somehow experienced it on Sunday almost as uncharted territory. I remembered it as part travelogue and part personal essay, and it certainly is. But I also realized that everything anyone could ever hope to know about Japan lies between the covers of that slender book. Richie displays an encyclopedic breadth and depth in explaining each aspect of Japan's culture. To take just a few of many examples, he gives cogent explanations of both Buddhism and Shinto, and he spends quite a bit of time talking about folklore. The names Momotaro, Taro Urashima, and Benten pop up frequently.

Whatever I've learned over the past few years with Joy o' Kanji seems to have been in The Inland Sea already! I almost feel that I should start all research by turning to that book.

And then he died. It happened on Tuesday, February 19, in a Tokyo hospital. He was 88. Having survived five heart attacks and a near-death bout with pneumonia, he probably surprised no one by dying. Because I knew that he was old and unwell, I felt very little when I heard the news. It just made sense.

But I still hadn't found that elusive quotation about the pylon, and so I spent six more hours with him yesterday, finishing my here-and-there perusal of The Inland Sea, finding the quotation on the next-to-last page (of course!), and then returning to the first half of the book, still finding the text unfamiliar in many places. (Why?!)

By the end I felt as crazed as I do after any deep immersion (and the attendant withdrawal from the world). On top of that, I was grief-stricken. How can you read The Inland Sea and not feel that Richie is one of your closest friends? He's a terrific traveling companion—funny, entertaining, insightful, and above all perceptive about everything from the look of a place to the ways in which people conflict and connect with one another. Hmm ... I should recast those sentences in the past tense. He's gone now. Hard to believe. And yet the gift of any great writing is that it's timeless, and it makes the author immortal. So there it is. I don't need to grieve because he's just as alive in his books as he was decades ago when he began to excite the West about what Japan has to offer.

Last night in a Nepalese restaurant, just as I was telling my husband everything that had passed through my mind that day in terms of Richie, we glanced out the window and saw my publisher, Peter Goodman, sauntering by. I waved, then ushered him into the restaurant. Surprised, he nevertheless complied. "I've been thinking of you all day," I blurted out. How could I not? Peter introduced me to Richie's works all those years ago—and later to the great man himself at an event in Berkeley where Richie spoke.

"Whatever the topic was, Richie got there first," said Peter last night, neatly summing up the dilemma facing anyone who has ever tried to write about Japan.

There's really just one thing Richie didn't cover. Like all his works, The Inland Sea was completely devoid of kanji because he could barely read Japanese. This boggles my mind, as he was an insanely literate man in terms of English. What was it like to live in Japan for decades, unable to read the signs around him? I actually had a chance to ask him about this at the Berkeley event, but the moderator cut me off before I finished my question. You can see the full event online, and I recommend it. You'll see not only Richie but also Peter, who gives a talk at the beginning. My question, which is all but inaudible (just as I am invisible!), comes at 1:10:45. Richie answers it until 1:13:25, and it's a great answer—just not quite what I hoped to learn.

Despite spending his days and nights speaking Japanese at a level that astounds me (at least judging from the conversations he relates in the book), he didn't lose his command of English, as so many expatriates in Japan seem to do. Instead, he maintained an English vocabulary that surpasses that of the most articulate people I know. Yesterday as I reread The Inland Sea, I kept an English dictionary open so I could find out just what he meant by "lozenge" (a diamond shape), "rapine" (plunder), "derrick" (a hangman), and "cant" (insincere expressions of enthusiasm).

I also kept a Japanese dictionary close at hand. On top of everything he accomplishes in that book, he spends a great deal of time teaching Japanese! He does it in romaji, without the use of macrons to differentiate long vowels from short ones, so I came upon a host of unfamiliar words and puzzled over what he was truly saying.

I'm talking about terms such as zori, which corresponds to this:

草履 (ぞうり: Japanese sandals) grass + shoes

And haori, which I've heard of but have never seen in kanji:

羽織 (はおり: formal coat) feather + weave

And a sliding door that he referred to as a fusuma:

襖 (ふすま: Japanese sliding screen), a non-Joyo character

And a host of casual expressions that he translated in a way that feels like a gift:

Sore de komatte iru no desu: That's just the trouble.

それで困っているのです。

Dete shimaimashita: She just up and went off.

出てしまいました。

Kanojo wa iya datta: She didn't like it.

彼女は嫌だった。

So iu onna ja nai to itta: She told him that she wasn't that kind of girl.

そいう女じゃないと言った。

Mo awanakutemo ii to itta: She said they needn't meet again.

も会わなくてもいいと言った。

In another section of the book I very much appreciated this sentence: "Kinoe is an ippon-michi (one-street) town" (p. 180). So simple! He could easily have omitted the Japanese. But by slipping it in there, along with the definition, he taught us how to say 一本道. The 一本 refers to one long, thin thing, in this case the road. What a beautiful, clear image. I've never heard of a "one-street town" in English, only a one-horse town and a six-stoplight town, as I used to think of my stiflingly small college town.

Speaking of counters for long, thin things, it was from Richie's Inland Sea that I first learned about that concept years ago, and the lesson has always stayed with me. He asked for directions to an inn and heard the answer "two." Not surprisingly, Richie felt confused. Two what? He mused that the man "had used hon, the counter for, among other things, long, thin objects, such as umbrellas and cucumbers. After it was explained, I realized that the people on this island do not reckon length in terms of meters but something else. Just as the natives of Mexico divide space into the time it takes to smoke a cigarette, these island people reckon by the relatively recent innovation of electric-line poles. My inn was two poles away" (pp. 22–23).

Even with his incredible gift for Japanese, Richie also struggled to understand the language at times, and not just because people were speaking in that sort of unexpected way. In a particularly compelling part of the book (pp. 118–122), he arrives on an island and asks everyone where he can find something he has heard of: a stone formation that naturally resembles a cat. This cat was apparently part of a folktale in which someone threw him away, so Richie uses 捨てる (すてる: to throw away). However, his Tokyo-accented すてる is mistaken for 知ってる (しってる: to know), so people think he's looking for a cat he knows, not a discarded cat. Initially unable to think of the term for "stone statue," he eventually produces 石像 (せきぞう). That helps a bit. But when a fisherman helps him locate what he's seeking (because it's actually a boat ride away), the guy says that Richie should have asked for the 猫の形をした石 (ねこのかたちをしたいし: stones in the form of a cat). Frustration comes on the heels of more frustration when it comes to communicating in Japanese—that feels familiar! Even the mythical stumble sometimes!

I'll leave you with a quiz inspired by Richie's romaji. See if you can figure out the kanji corresponding to the romaji:

1. "'The moon's set,' she said. 'In a day or two it will be full. It will be jugoya'—the full moon, a word used only in the autumn" (p. 230).

2. "I, using my most polite grammar, said that I would have a whisky and water—'Mizuwari o itadakimasu.'" (I'm just asking about mizuwari here.)

3. "[The place name] Ikuchi, written with the characters meaning 'living' and 'mouth,' can also be read Seiko, which has many meanings—a kind of cattle, a prisoner of war, or by extension, a slave" (pp. 156–57).

I'll block the answers with a preview of the new essay 1164 on 峡, which has a bit to do with the Inland Sea!

1. 十五夜 (じゅうごや: 15 (1st 2 kanji) + night) means "night of the full moon; the night of the 15th day of the 8th lunar month," to use Breen's definition.

2. 水割り (みずわり: water + dilution) means "alcohol (usually whiskey or shochu) diluted with water."

3. 生口 (living + mouth) can be read as いくち (only when it's a place name) or as せいこう. "If the etymology of a Japanese place name is too confused, it is good to pause and search further. One is likely to come across old bones, skeletons, some horrid and hushed-up affair" (p. 156), wrote Richie before exposing the very skeletons associated with the name Ikuchi.

In the end, it seems that Richie, too, delved into the meanings of kanji! He covered it all!

Comments