169. The "Gate" Radical: 門

The "gate" radical 門 provides a soothing simplicity. Its eight strokes are nearly symmetrical, as is appropriate for a pictograph of a "closed double gate or a door."

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

That's what the newer edition of Henshall says about the origins of this shape:

門 (211: gate; division; student; sect; family; "gate" radical)

As an autonomous kanji, 門 carries two Joyo readings, モン and かど. So it is that one can call the 門 radical もん or かど. That name applies if we're talking about 門 as the radical of the 門 kanji. When it comes to 門 as the on-duty radical in 10 other Joyo kanji, it would be more accurate to use this name:

門構え (もんがまえ or かどがまえ)

The 構え means "enclosure." (For more on this nomenclature, go to Radical Terms, see the section "Radical Positions," and look at position 5.) Indeed, the 門 shape wraps around the inner elements in all these kanji:

間 (92: interval; space; between; relationship; timing; room)

開 (241: to open; begin; hold (an event); adjournment)

関 (444: related to; entrance, barrier; sumo wrestler; to affect)

閣 (822: magnificent tall building; government cabinet)

閉 (968: to close)

閲 (1023: to review, inspect; read)

閑 (1109: idle; quiet)

闘 (1659: to fight, compete; contend with)

閥 (1710: clique; clan)

闇 (2121: dark, dim; illegal; chaos)

I'm glad the gates protect the innards so well; many of those interior shapes are themselves autonomous kanji!

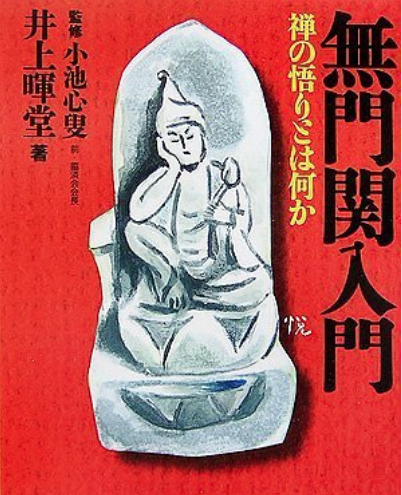

Gateway to Enlightenment

Look how neatly the three "gate" radicals stack on the right side of this book:

We're treated to two instances of 門 and one of 関 (444: related to; entrance, barrier; sumo wrestler; to affect) in this title:

「無門関入門」

Introduction to the Gateless Gate

入門 (にゅうもん: introduction)

I've defined the only definable term, 入門. The first bit, 無門関 (むもんかん: lit. "the gateless gate"), is actually the title of another work, a classic full of Zen riddles that show the intrinsic absurdity of our existence. That's according to Damian Flanagan in a terrific Japan Times article about the 門 kanji. He says that by providing such content, it's as if the book「無門関」 itself is acting as a gateway to enlightenment.

The book shown above should also be that kind of gateway. Here's the subtitle:

「禅の悟りとは何か」

What Is Zen Enlightenment?

禅 (ぜん: Zen); 悟り (さとり:

enlightenment); 何 (なに: what)

The Shape of a Gate

For awhile something has bothered me about 門. If it is indeed a pictograph of a closed double gate or a door, then the gate that inspired the picture must have looked simple, perhaps like this:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

A gate in Berkeley, California.

But how Chinese is that? The traditional Chinese gate, the paifang, features multitiered roofs, supporting posts, and archways. Here's one example:

Photo Credit: Vmenkov

Wikipedia traces the roots of sacred Asian gates back to the Indian torana, which has a structure similar to that of a torii. Indeed one of the most famous toriis in Japan is at Itsukushima Shrine (in Hiroshima Prefecture) "where the Indian Hindu goddess Saraswati is worshipped as the Buddhist-Shinto goddess Benzaiten," according to the same Wikipedia article.

In Japan, much more elaborate gates that lead to sacred spaces also reflect Asian aesthetics. Take, for example, Kaminarimon in Asakusa (in Tokyo). Even secular spaces can have large, impressive gates, such as Akamon at the University of Tokyo and Kuromon at the Tokyo National Museum. Both elaborate structures once sat outside old mansions.

All of this is a far cry from the saloon-door look of the wooden gate in the next-to-last photo above. But 門 goes back thousands of years and may have emerged at a time when gates were much simpler in China. Either that or someone didn't want to create a pictograph as complex as a multitiered paifang—not that the Chinese have shied away from intricate characters!

The Gates in Our Kanji

Let's explore why there are gates in some of the kanji containing our radical. All of these etymologies come from the newer edition of Henshall.

間 (92: interval; space; between; relationship; timing; room)

This character once depicted the moon as seen through a gate, but the 月 (moon) changed to 日 (sun). That component may or may not be a phonetic. One scholar thinks the 月 contributed meaning, making the overall character represent "gate with an opening through which moonlight can be seen."

開 (241: to open; begin; hold (an event); adjournment)

The radical means "gate," and the inner element represents one of two things, depending on which scholar you ask:

1. The torii-like shape means "to face, oppose," so the whole character depicts "the two leaves of an open gate facing each other."

2. The internal component depicts "two hands reaching out to remove the crossbar" of the gate.

閉 (968: to close)

Our radical means "gate" or "door." The inner part was originally 才, not オ, and Henshall presents three interpretations about what it means here:

1. The 才 conveys "to obstruct," and the whole 閉 character represents "to close gates."

2. The inner part is a phonetic with the associated sense "timber," making 閉 mean "to close off the entrance with timber."

3. The 才 contributes meaning—specifically "a piece of wood with a prayer receptacle attached."

So far we've consistently seen etymologies about wooden gates that open and close. Similarly, the origin stories for these three kanji involve mechanisms that bolt gates closed:

関 (444: related to; entrance, barrier; sumo wrestler; to affect)

閣 (822: magnificent tall building; government cabinet)

閑 (1109: idle; quiet)

This is logical but not that exciting! Let's shake things up a bit with two etymologies that provide surprises:

闘 (1659: to fight, compete; contend with)

The original radical shape was 鬥, showing two people (or possibly two beasts) facing each other or locked in fighting. The inner part also looked different and represented "to cut a tree with an ax," conveying something to do with cutting, fighting, or hitting. (I can't make sense of Henshall's comments there.)

閥 (1710: clique; clan)

The radical means "gate" and by extension means "house, family" here. The 伐 means "to attack, cut down" and serves as a phonetic with one of two associated senses:

1. It may convey "to stand out," in which case 閥 means "house or family that stands out from ordinary people," leading to "fine lineage" as an extended meaning.

2. The interior part could contribute the sense "achievements, distinguished service," in which case 閥 means "house or family of multigenerational achievements."