167. The "Metal" Radical: 金

The eight-stroke "metal" radical has a great deal in common with the autonomous 金 kanji:

金 (14: metal (esp. gold); money; Friday; Venus)

The "metal" radical takes its English name from the primary meaning of this kanji. ("Money" and "gold" are alternate radical names, again based on the definitions of 金.)

Just as the character has the kun-yomi of かね, the Japanese radical name is かね.

We can use that name when speaking of the radical in the 金 kanji itself. The same applies to the radical in this character:

釜 (1950: metal pot)

In 31 other Joyo kanji, the on-duty 金 radical lies on the left side of a character, as in these examples:

録 (611: record, register)

鋭 (1018: sharp, acute; excellent)

鈍 (1671: dull; slow)

銘 (1847: inscription; established name; to engrave on one's mind)

In such cases (that is, most of the time), we can refer to the radical as かねへん. The -へん means "radical on the left side of a kanji."

By the way, did you notice a pattern among the definitions of those four kanji?

Etymologically, both 録 (611) and 銘 (1847) have to do with inscribing words in metal, and that meaning is still relevant to both kanji. "A metal inscription is an enduring record," says Henshall in his etymological analysis of 録, which primarily means "record."

Meanwhile, 鋭 (1018) literally represents a "sharp-edged tool/item," says Henshall in his newer edition, attributing that sense to the metal on the left and the shape on the right, which might convey the associated sense "sharp" or "small and sharp." The Japanese use 鋭 to describe not only physical sharpness but also the keenness of senses and the nimbleness of minds. With 鈍 (1671), says Henshall in that edition, we instead have a blunt and rounded blade on the right. By extension, 鈍 can represent dimwittedness. Thus, these two kanji are antonyms, all thanks to the properties of the metals they contain!

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

In Salzburg, Austria, a sign for a Chinese restaurant refers to 金魚 (goldfish) while emphasizing the goldenness of 金. So does this sign in Kichijoji, a section of Tokyo:

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

I wrote about this restaurant sign in essay 1028 on 猿 (monkey), a free sample essay. There I said that when I showed this picture to several Japanese people, all of them read it properly as 金の猿 (きんのさる: Golden Monkey). I asked how they knew to use the on-yomi キン, rather than かね, even though 金 is standing alone. They shrugged and said it simply sounded more natural. Plus, the golden background brought gold to mind. As one explained, “’Golden monkey’ makes much more sense than ‘monkey of money.’” I was actually amazed that everyone could identify the messy 猿 with no problem. Perhaps the picture of the monkey helped!

Your Basic Metals

In Exhibit 50 of Crazy for Kanji (pages 114–115), I explored the theme of metal in Japan because I was intrigued by the kun-yomi of kanji such as these:

銀 (263: silver; abbrev. of "bank"), しろがね, which literally means "white metal"

鉄 (353: iron), くろがね, which literally means "black metal"

銅 (758: copper), あかがね, which literally means "red metal"

All three words give colorful indications of the perceived colors of these metals. Incidentally, the がね is the voiced かね (the yomi of 金).

As I wrote in the book, the Japanese have used iron tools since around 300 BCE, having borrowed that manufacturing knowledge from China. At that point Japan was at least seven centuries away from borrowing characters from China, so although the Japanese had iron and a word for that metal, it would be eons before they could represent that word in kanji!

When they did acquire characters for metals (and for everything else), they could have quite logically written しろがね as 白金, but instead that corresponds to はっきん, "platinum." The Japanese matched their very descriptive spoken terms with characters and words that the Chinese had already created for various metals.

In the same exhibit, I also touched on these two kanji:

鉛 (1029: lead), which turns out to be another "white" metal (etymologically speaking), because its right side phonetically expresses "white," says Henshall. The kun-yomi of 鉛 is なまり, which breaks with the "color + がね" scheme.

鋼 (864: steel), which has the kun-yomi of はがね. That sounds like it might fit the "color + がね" scheme but doesn't. Instead, according to Daijisen and Kojien, はがね comes from 刃金 (blade + metal), which translates as "steel." In fact, Breen shows that 刃金 is an alternate rendering of 鋼. In that kanji, the 岡 means "hill" and contributes the sense of "formidable" and "strong," producing a composite meaning of a "strong/formidable metal," says Henshall.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

A Japanese herbal shop in Tokyo starts with back-to-back instances of our radical! What's more, 金 (キン) and 銀 (ギン: silver) rhyme! The word 金銀花 is another name for スイカズラ (忍冬: Japanese honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica). This vine bears white flowers that turn yellow in a few days, which is where the 金銀 comes from, according to Daijisen; white corresponds to 銀, and yellow corresponds to 金.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

This sign starts with our radical. (Actually, that's been true in all the photos I've shared thus far! That seems auspicious somehow!) Here are the largest kanji:

鉄製茶器

iron teapots

鉄製 (てっせい: made from iron);

茶器 (ちゃき: tea utensils)

Note that 鉄 (353) has not only the kun-yomi of くろがね but also the on-yomi of テツ, as in 鉄道 (てつどう: railroad), literally the "iron road." In the reading of 鉄製, てつ becomes contracted to てっ.

Things Made of Metal

Surveying the Joyo kanji containing our radical, one realizes just how much we need metal on a daily basis.

With metal, we buy things:

銭 (734: money; coin; fee; small monetary unit)

We repair and inject things:

針 (905: needle)

We secure things:

鎖 (1286: chain, link)

錠 (1423: lock; pill)

鍵 (2002: key; lock)

We cook things:

鉢 (1705: bowl; flowerpot; crown of head)

鍋 (2088: cooking pot; pan)

Most of us don't use the following tools, but some people do, wielding them to bring down vegetation or living creatures:

鎌 (1980: sickle)

銃 (1365: gun)

By contrast, we all use this instrument, and some of us do so far too often:

鏡 (462: mirror; lens; scope)

By the way, the next kanji also has to do with mirrors:

鑑 (1117: model, material; consideration; mirror)

That is, this character combines "metal" with "to watch." The right side literally means "to stare at one's reflection," says Henshall. In Chinese, he notes, 鑑 can still mean "metal mirror," but in Japanese it evolved to mean "to scrutinize" and "to take note of; heed." He makes one more cool point; the Joyo kun-yomi かんがみる derives from かがみ (mirror) + みる (to look). Actually, 鑑 also has the non-Joyo kun-yomi of かがみ, and as such it means "model, pattern," as in, "He's the perfect model of a doctor." In this sense, 鑑 is a figurative mirror of perfection.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

An optical company in Shinjuku (a section of Tokyo) shows us how our radical looked in the olden days. It really hasn't changed a bit! To read this sign, go from right top to right bottom, left top to left bottom:

眼鏡市場

眼鏡 (めがね: glasses);

市場 (いちば: market)

Thus the name means "Optical Market." The kanji underneath serve as a kind of eye test, I suppose! They're all in seal script.

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

At a temple in Nikko (Tochigi Prefecture on Honshu), a box for collecting donations bears this inscription:

賽銭 (さいせん: monetary offering) temple offering + coin, money

Such a box is called a 賽銭箱 (さいせんばこ), in which 箱 means "box." The first kanji is non-Joyo. And as you know, 銭 (734) is "coin, money."

By the way, the next kanji has a similar meaning:

釣 (1592: fishing; change (for payment); hanging; to lure)

As the definitions indicate, people use this kanji for both catching fish (with the "metal hook" that 釣 most likely represents, says Henshall) and the sort of change you receive after paying 1,000 yen for an item that cost 700 yen.

Temples should probably put 釣 on their boxes instead. After all, they're fishing for donations!

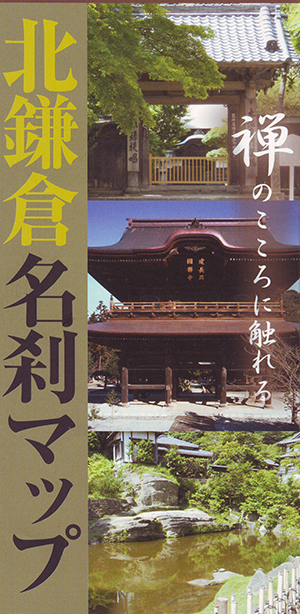

The place name Kamakura (鎌倉, かまくら) contains our radical. The first kanji is 鎌 (1980: sickle), and 倉 is "warehouse." This map is for 名刹 (めいさつ: famous temples) in north Kamakura (北鎌倉), where 北 (きた) means "north."

The white bit down the right is as follows:

禅のこころに触れる

To feel the heart of Zen

神 (ぜん: Zen); こころ (心: heart); 触れる (ふれる: to be moved by)

Doing Things with Metal

We couldn't have so many metallic items in our lives unless there were ways of casting metal into desirable shapes. The following kanji involve that activity, as Henshall explains in his newer edition:

鍛 (1569: to train; forge), where the right side phonetically expresses "hit, strike," giving us "beat and temper heated metal."

鋳 (1586: casting, minting), which etymologically relates to "melt and pour metal" or "pour molten metal everywhere within a mold"—that is, "casting."

錬 (1933: to refine or work (metals); to train), where the right side—originally 柬 (to select)—phonetically conveys "soften," "liquefy," or "process, treat." Thanks to those senses, the overall character etymologically represents "to soften and forge metal," "ore liquefies," or "treat metal (by heating)," respectively.

Photo Credit: Yoshikazu Kunugi

A bell at Daizen-ji Temple in Katsunuma in Yamanashi Prefecture on Honshu. The Japanese represent a huge temple bell with this kanji:

鐘 (1414: bell)

The next kanji symbolizes another type of bell:

鈴 (1921: bell)

This kind typically has a metal ball inside to produce a ringing sound and a slitted exterior to enhance that sound.