153. The "Badger" Radical: 豸

The seven-stroke "badger" radical 豸 would seem to have everything to do with animals. That is, the non-Joyo autonomous kanji 豸 means "snake," "legless insect," or "slowly crawling animal." Furthermore, the 豸 radical is named after an animal. To wit:

• The primary radical name むじな (or むじなへん when the radical appears on the left side of a kanji) translates as "badger." The yomi むじな comes from the reading of the non-Joyo 貉 (むじな: badger).

• Nelson mentions あしなきむし (reptiles) as another way of referring to this radical. However, very few sources reflect that radical name.

• He provides the nickname "clawed dog" to help people distinguish between radical 153 and the English names of these two radicals:

radical 87, 爪, the "claw" radical

radical 94, 犬, the "animal" radical, also known as the "dog" radical

The 豸 radical is also animalistic in 貌 (2110: appearance); that left-side shape means "beast," according to Kanjigen. The right-side component (and phonetic) 皃 represents "person," depicting that person's head and legs. All together, 貌 means "outline of a person or animal's appearance," though no one uses 貌 for an animal's appearance now.

By the way, 貌 isn't just a outlier that we can easily dismiss with its lack of beastliness; it's the only Joyo kanji to include the 豸 radical!

The 豸 shape does pop up as a component in two other Joyo kanji, but those characters also have no connection to animals:

墾 (1281: cultivating land)

懇 (1282: friendly)

For what it's worth, though, most non-Joyo kanji with this radical do remain in the animal kingdom, as we saw with 貉 (badger). Here are other examples:

豹 (leopard, panther)

豺 (jackal)

豼 and 貅 and 貔 (brave heraldic beast)

貂 (marten, sable), a furry mammal

貍 (raccoon-dog), read as たぬき, though the non-Joyo 狸 is the "real" tanuki kanji

貎 (lion; wild beast; wild horse)

貘 (tapir)

So on the very rare occasions in which you encounter the 豸radical, you should still be on the lookout for sharp fangs and flashing eyes!

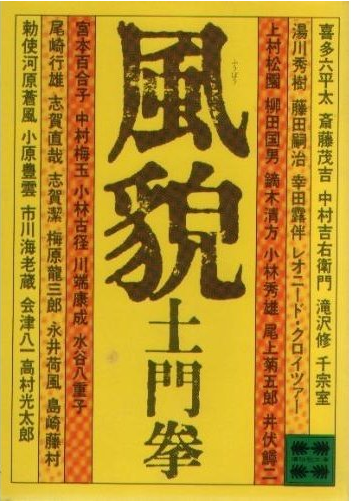

The cover of this book features a tempting array of kanji, including the large word 風貌 (ふうぼう: looks; appearance). Again, though, this has nothing to do with animals. On the contrary, the work is a collection of people's portraits. They're by photographer 土門拳 (どもん けん: 1909–1990), whose name appears on the cover beneath 風貌.

One of the most renowned Japanese photographers of the 20th century, Domon was a photojournalist but took copious photos of Buddhist temples and statues. Wikipedia explains that he came into his own when the war ended, documenting the aftermath by focusing on the lives of ordinary people. He went for realism in his photos, rejecting drama, poses, and artiness and aiming instead for a direct connection between his camera and the subject. His powerful postwar captures include images of Hiroshima bombing survivors, residents (especially kids) of a poor coal-mining town on Kyushu, and children at play in Tokyo.

After two strokes in the 1960s confined him to a wheelchair and prevented him from even holding a camera, he began focusing on photographing temples.

The Ken Domon Museum of Photography opened in 1983 in Sakata (in Yamagata Prefecture on Honshu), where he was born. The museum (the first in Japan dedicated to photography) contains 70,000 pieces of his work.

By the way, essay 2110 contains a different version of the book cover, but I couldn't bear to let this one slip through my fingers, so here it is!