120. The "Thread" Radical: 糸

The "thread" radical 糸 has wound up in a staggering number of Joyo kanji. It's on duty in 63 of them, including this autonomous kanji:

糸 (27: thread)

Clearly, the radical name in English comes from the meaning of that kanji. Nelson indicates that people also refer to 糸 as the "silk" radical, but we won't.

He mentions, too, that people have nicknamed 糸 the "long thread" radical to distinguish it from this one:

幺 (radical 52: "short thread")

But we'll use "thread" for the 糸 radical.

By the way, 糸 has twice as many strokes as its "rival"—six versus three.

The image on the left shows 糸 (27: thread) as a seal-script character, and the other two reflect how it looked as a bronze character. The shape originally depicted a "skein of yarn," says Henshall, who is the source of all etymological information in this Radical Note.

Japanese Names and Positions of the "Thread" Kanji

When the on-duty 糸 radical appears in a kanji, it's almost always on the left, as is true in these cases:

絵 (89: picture)

細 (284: slender)

終 (306: end)

We can refer to that left-side radical as いとへん (糸偏).

If the radical is somewhere else in the character, the term いと will do. That's the Joyo kun-yomi of the 糸 kanji.

Here are some characters in which the 糸 radical is not on the left:

素 (737: element)

系 (844: system)

緊 (1179: to tighten)

繭 (1223: cocoon)

累 (1917: accumulation)

In all cases, 糸 is at the bottom, except in 繭 (1223), where it's tucked inside the left "windowpane" (which is my take on that shape).

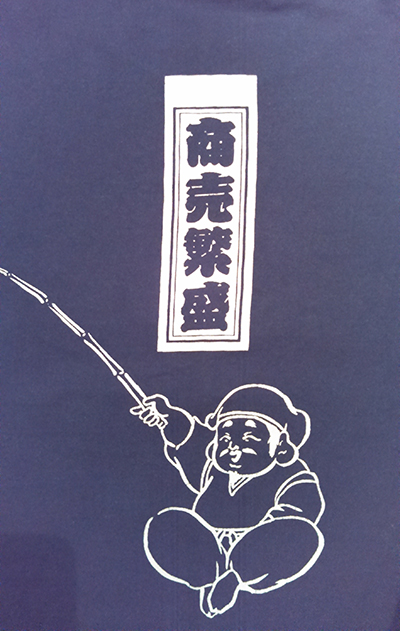

Photo Credit: Kevin Lew

When I saw these kanji on the back of a classmate's shirt one day in yoga class, I could think of little else. If only the man would hold steady so I could get a good look at the dense clusters of strokes! I finally asked him to take a photo of the shirt, and he kindly obliged. As I now know, these are the characters:

商売 (しょうばい: business)

繁盛 (はんじょう: prosperity)

Our radical sits at the base of 繁 (1720: to thrive), combining with 盛 (to prosper) to produce "prosperity."

The common phrase 商売繁盛 means "thriving, prosperous business; rush of business," and people use it to say, "Business is good." The idea is that good business (商売) involves becoming more and more prosperous (繁盛).

The man with a fishing rod is Ebisu (恵比寿, えびす), one of the Seven Lucky Gods (七福神, しちふくじん). He's often considered to be the god of 商売繁盛.

The "Thread" Radical in Kanji for Handicrafts

It's not at all surprising to find the "thread" radical in kanji representing handicrafts such as weaving, knitting, sewing, and spinning:

織 (720: to weave)

編 (785: to knit)

縫 (1804: to sew)

紡 (1814: to spin)

It is perhaps more unexpected that 編 (785: to knit, braid; edit, compile; organize; volume, literary work) primarily means "to knit"; I most often see it as "edition," as in 新編 (しんぺん: new edition). Henshall gives a detailed explanation of how one character came to represent both meanings. The short story is that the components of 編 combine to mean "to bind together in ordered arrangement using threads," branching off into two definitions—namely "to knit" and "edit, compilation."

Photo Credits: Eve Kushner

As you might have guessed, these artisans are not in Japan! Rather, I met them in northern Thailand at an ecovillage where they were making fabulous silk weavings.

If you long to return to a Japanese context, that's fine! The Japanese have their own impressive weaving heritage and techniques!

As long as we're traveling around Asia, the etymologies of two characters reflect weaving techniques that must have existed in ancient China. To understand the history, you need to know these words:

the warp: lengthwise threads on a loom

the weft: crosswise threads on a loom

Both terms factor into Henshall's analysis of this character:

経 (658: to pass through, experience; elapse; economics; sutra; longitude)

The radical represents "thread," of course. The right side of 経 used to have a different shape and meant "warp," he said. Because warp threads act as guides for weft threads, 経 came to represent "guiding principles," including "sutras." That is incredibly cool! "To pass through" and "longitude" are associated meanings, which is interesting, given that "to pass through" has become the primary definition.

In the next character, we need to take both weaving and phonetics into account:

緯 (1009: latitude; crosswise thread in weaving)

Whereas the radical again means "thread," according to Henshall in his newer edition, the 韋 originally meant “move away” or “patrol round an area” and phonetically expresses “surround.” Thus, 緯 represents “thread that surrounds (the vertical thread),” which refers to the weft relative to the warp.

Good Stories

Who doesn't love a good story, particularly a good etymology?! I really like Henshall's explanations of how the following characters acquired their meanings:

紙 (132: paper)

The radical means "silk thread" in this case, and the 氏 (originally "ladle") acts phonetically here to express "smooth." This character originally represented "smooth silk" and by extension "smooth cloth." People once used cloth as a writing material, so this character came to mean "writing material" and therefore "paper."

線 (329: line)

The radical means "thread," and the 泉 (usually "source, spring") phonetically expresses "slender." Eventually, "slender thread" became "line." One sees this kanji in train stations and at the end of 新幹線 (しんかんせん: Shinkansen). That's quite a long journey for a slender thread!

紹 (1400: introduction)

The "thread" radical combines with 召 (to summon, partake). The right-hand side acts semantically and phonetically to express "to join," so 紹 originally meant "to join threads." People then began using it to mean "to bring two things together," which can extend to "introduce." At least, that's one theory that Henshall proposes in his newer edition.

Photo Credit: Kayoko Kurimoto

In Shinto shrines, this large rope cordons off consecrated areas and supposedly wards off evil. The Japanese refer to this sort of rope as a 注連縄 (しめなわ), which you can read about on Wikipedia. The third kanji is 縄 (1420: rope, straw rope).

This photo is from Izumo Taisha Shrine in Shimane Prefecture on Honshu, where the 注連縄 weighs about five tons!

Gathering and Tightening Threads

Like 紹, several kanji with 糸 have etymologies that involve gathering or joining threads. Here's an example of what I mean:

続 (536: to continue; sequel, successive)

This kanji combines "thread" with "to sell," though the 売 here (originally 賣) phonetically expresses "to join" and "equivalence." If you "join threads of equal length," that yields "continuity" and "succession."

For many other kanji in the 糸 group, the etymology has to do with tightening and loosening cords and cables. Here's another example:

約 (591: approximately; promise, treaty; to contract; summarize; economize)

As with 紙, we have "thread" + "ladle"! In this case, the 勺 phonetically expresses "to tie tightly." Thus, 約 meant "to tie threads tightly (into a knot)." Figuratively, this came to be applied to "binding agreements" and "to tighten up" (that is, to remove inessential elements), which is to say "to summarize" and then "approximation."

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

In Sydney, Australia, a sign saying 横綱 (よこづな: grand champion in sumo) brings our 糸 radical to life with the image of a rope! The second kanji is as follows:

綱 (1264: rope; main points, gist)

The word 横綱 breaks down as horizontal + rope. A yokozuna wears a rope (綱, つな) around his waist as a visible symbol that he has achieved the highest rank in sumo.

As a Wikipedia article explains, there's a similarity betwen the rope of a yokozuna and a shimenawa (the huge rope featured in the last photo). In fact, says that source, there are two legends about how the yokozuna's rope originated with the shimenawa. In one account, a ninth-century wrestler tied a shimenawa around his waist as a handicap and dared anyone to touch it, thereby creating sumo in its current form. In the other account, legendary wrestler Akashi Shiganosuke tied a shimenawa around his waist in 1630 as a sign of respect when visiting the emperor.

Photo Credit: Anne Hill

In one JOK Notebook post I wrote about my confusion about walking into a bathroom labeled 紳士, only to see a urinal. As I realized, 紳士 (しんし) means "gentleman."

The sign above is for 紳士服 (しんしふく: men's clothes). How thoughtful of them to feature our "thread" radical again in a sizable way in 名紳 (めいしん), the name of a suit manufacturer. We've been treated here to two instances of this kanji:

紳 (1439: gentleman)

And what's the connection between our radical and men? Henshall explains 紳 this way: This 糸 means "cloth" (not "thread"), whereas 申 (to say) acts phonetically to express "to pull/stretch" here. Cloth that is pulled or stretched is a "waistband/belt." That came to be associated with "gentleman"!

Colors

Our radical appears in kanji representing four colors! I'm talking about these:

緑 (412: green)

紅 (862: crimson, red)

紺 (1279: dark blue)

紫 (1320: purple)

Photo Credit: Eve Kushner

In Melbourne, Australia, this sign starts with 紅 (862: crimson, red). The three red characters mean "red ant" in Chinese. Sound appetizing?!