The Cryptogram Spirit

Let's start with sample sentences from various essays. For the moment, I won't supply clues, but that'll change as we progress:

家々の軒先には旗が掲げられていた。

彼らは女王がおいでになるので旗を掲げた。

意味のない流行言葉を使わない。

この段階を踏まえ、抑圧という概念をさらに詳細に検証していくことになります。

See what you can do. And more important, see how you feel right now. If there's anything you don't know in these sentences, what emotions arise? Frustration? Impatience? A sudden urge to write it all off—kanji, Japanese grammar, and maybe the whole Japanese language?

Perhaps I shouldn't admit this, but my typical response when I see most Japanese text is (even now!) to avert my eyes and move on to the next item in my Facebook feed (because that's typically where I encounter Japanese writing). I can't tolerate a feeling of defeat. I can't stand the inevitable self-recrimination. I give up before I even try.

Isn't that terribly strange, given that kanji is the source of all passion and meaning in my life? My tendency seems quite odd to me, so I can only imagine how it would seem to others.

But if I'm curious about the person who wrote that Facebook status, if I really want to know more about who that person is and how he or she expresses himself to other native speakers, I eagerly tear into the message and try my best to decode it.

This reaction—aversion or eagerness—governs a great deal about how well I do with kanji at any given time.

In a moment I'll tell you why I'm bringing this up today. For now have another go at those sentences. This time I've defined the vocabulary:

家々の軒先には旗が掲げられていた。

家々 (いえいえ: every house); 軒先 (のきさき: front of a house); 旗を掲げる* (はたをかかげる: to hoist or fly a flag)

彼らは女王がおいでになるので旗を掲げた。

彼ら (かれら: they); 女王 (じょおう: queen); おいでになる (御出でになる: to come, stated in honorific language)

意味のない流行言葉を使わない。

意味 (いみ: meaning); 流行言葉 (はやりことば: buzzword; popular expression; faddish word or phrase); 使う (つかう: to use)

この段階を踏まえ、抑圧という概念をさらに詳細に検証していくことになります。

段階 (だんかい: level; stage); 踏まえる (ふまえる: to base on); 抑圧 (よくあつ: oppression); 概念 (がいねん: concept); さらに (even more); 詳細に (しょうさいに: in detail); 検証 (けんしょう: examination)

The translations will appear eventually. First, more chitchtat.

A certain theme keeps presenting itself, and it has seized my attention. I've recently seen two movies about British geniuses who solve unthinkable scientific problems: A Theory of Everything (the Stephen Hawking biopic) and The Imitation Game (about Alan Turing, who helped to break a Nazi code during World War II, shortening the war by as much as two years). I've also gotten hooked on the TV show The Big Bang Theory (after years of seeing snippets and thinking it looked unappealing). The show follows socially maladjusted science geniuses, and this week I was particularly taken with an episode where the characters try to rekindle the joy of inventing things.

All this puzzle solving goes to the heart of what I've always loved about kanji. Reading it is a glorious act of decoding. It's a challenging game, a bang-your-head-against-the-wall source of frustration, and a triumphant conquest. At least, when I can reconnect with a childlike sense of playfulness, I feel all those things while deciphering Japanese text. When I instead read with the expectation of total failure or effortless success, my experience is far from rewarding.

One scene in The Imitation Game took me to the very kernel of this feeling—the 核心 (かくしん: core, kernel + heart) as the Japanese say. A young Alan Turing sits under a tree with his best friend, talking about how life really only makes sense when they're solving cryptograms. At least, I think that's what they were saying; it's been six days since I saw the film, and dammit I really should have written this blog the day afterward, as my passions implored me to do, but there was essay 1409 to write....

I used to solve cryptograms as a kid. Actually, I didn't just solve them. I lay on the floor to do it. I worked away at them until they unraveled before my eyes, all the parts becoming clear. I had an enormous book of puzzles—maybe a thousand pages—and I must have spent years solving them all. I would open the book to random places at random times with no particular goal in mind. And then time would disappear, and my brain would light up, providing some of the best moments of my childhood.

In the movie, the young Turing and his friend write messages to each other in the form of cryptograms. My best friend and I similarly invented a code (one symbol for each letter of the alphabet), and we too passed notes that no one else could read (not that anyone tried, as I recall!). All those joys dovetailed perfectly—the thrill of having a secret language, the thrill of a close friendship, and most of all the thrill of decoding.

"This movie is about kanji," I kept thinking as I watched The Imitation Game. And of course it's about everything but that. It's about the horrors of World War II, about the development of computers, about the limitations of the human mind in every sense, and so much more. But for me the film was primarily about reconnecting to the spirit of solving puzzles, particularly the kind that involves decoding a written language.

Cryptograms have everything to do with patterns. So does kanji. The repeating radicals and components provide clues that are there for the taking. Why not drink it all in with an open mind and heart instead of creating so many emotional obstacles to understanding?

In this regard I often envision an open throat. Let me explain. Back in my college days, the bulk of people's entertainment involved drinking games. As I heard over and over, the way to chug beer most rapidly is to open your throat fully. (People say the same kind of thing about competitive hot-dog eating and maybe even sword swallowing.) I do best with Japanese when I "open my throat" so to speak, drinking in every spoken and written word as if I were insatiably thirsty.

Here at last are the translations I promised:

家々の軒先には旗が掲げられていた。

The fronts of the houses displayed flags.

家々 (いえいえ: every house); 軒先 (のきさき: front of a house); 旗を掲げる* (はたをかかげる: to hoist or fly a flag)

彼らは女王がおいでになるので旗を掲げた。

They hung out the flag for the queen's visit.

彼ら (かれら: they); 女王 (じょおう: queen); おいでになる (御出でになる: to come, stated in honorific language)

意味のない流行言葉を使わない。

Do not use meaningless, faddish expressions.

意味 (いみ: meaning); 流行言葉 (はやりことば: buzzword; popular expression; faddish word or phrase); 使う (つかう: to use)

この段階を踏まえ、抑圧という概念をさらに詳細に検証していくことになります。

From this point we go on to an even more detailed examination of the concept of repression.

段階 (だんかい: level; stage); 踏まえる (ふまえる: to be based on); 抑圧 (よくあつ: oppression); 概念 (がいねん: concept); さらに (even more); 検証 (けんしょう: examination)

In the last sentence, I get a kick out of この段階を踏まえる. The word 踏まえる (ふまえる) literally means "to have one's feet firmly planted on," but my proofreader says to translate it as "to base on." Either way, when you pair it with 段階, you can imagine someone so grounded that they're paradoxically ready to soar to the next stage or level—hence the translation "from this point (on)."

From this point on, I'm ready to embrace every kanji challenge as if I were a kid lying on the floor with an infinite book of puzzles to solve. Just think. If Alan Turing's love of cryptograms played an instrumental part in ending the war, maybe a love of kanji will lead to something useful in the end!

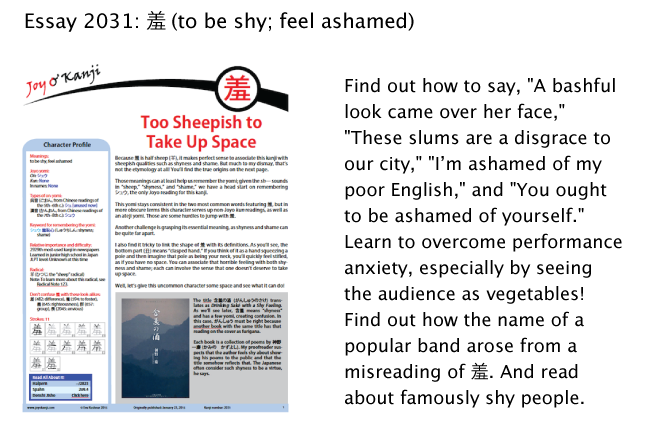

Here's a preview of the newest essay:

Have a great weekend!

Comments