A Rabbit or Rolling Over in Bed?

As editor of the Kanjidic, an electronic kanji dictionary used by countless web systems, dictionary programs, and apps, I regularly receive emails suggesting corrections and enhancements. Since the meanings and readings of kanji are fairly static, you may wonder why there would be changes at all. Well, the Kanjidic was initially assembled more than 20 years ago from various sources, some of which were not quite authoritative, and the odd error still lingers, especially among less common kanji.

One recent email mentioned the fairly rare kanji 夘, which in Kanjidic has the readings ボウ and う and the meaning “sign of the hare or rabbit in the Chinese zodiac." Small wonder it's rare! Citing the abridged edition of Morohashi, my correspondent thought the kanji should instead be read as エン and possibly ころがりうす and should instead mean something like “turning over in one's sleep."

Now, those were no simple editorial changes. In fact, if his assertion were correct, it would mean that the Kanjidic entry had gone totally astray, so of course I set about investigating the matter.

Before I go any further I should explain about Morohashi. It's the shorthand name for the monster kanji dictionary 大漢和辞典 (だいかんわじてん) that Taishukan initially published between 1955 and 1960. Largely the work of founding editor Tetsuji Morohashi (1883–1982), it consists of 13 volumes plus two supplements and covers about 50,000 kanji in incredible detail, including sources, readings, meanings, and compounds. Some scholars working with kanji think it relies a little too much on Chinese sources and not enough on Japanese usage. Be that as it may, when it comes to kanji you need to be very sure of your grounds before you stray too far from Morohashi.

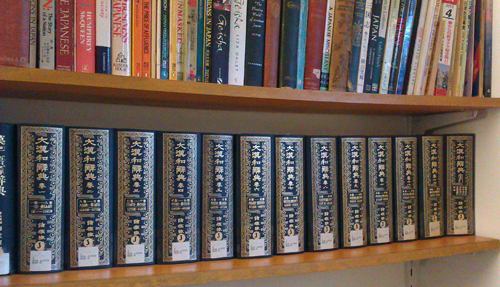

Photo Credit: Jim Breen

The original Morohashi volumes—all 13 of them! I acquired this set some years ago by rescuing it from a dumpster when a local university library disgracefully downsized its Japanese holdings.

I checked 夘 in Morohashi. The entry is brief, largely saying that 夘 is the same kanji as 夗 and has the reading エン. That source says almost parenthetically that 卯 is a different kanji altogether. Morohashi indicates that 夗 is read as エン and ころがりうす and means "turning over while lying down"—hence the suggestion from my correspondent.

As it happens, 夗 is virtually unknown in Japan. It is not in the Japanese character code standards, and I cannot find it in any other kanji dictionary.

But why does Morohashi mention 卯 at all? Well, 卯 is a more common kanji with, surprise surprise, the readings ボウ and う and the meaning "sign of the hare or rabbit in the Chinese zodiac." Most kanji dictionaries treat 卯 and 夘 as variant characters (異体字, いたいじ). For example, Spahn and Hadamitzky's The Kanji Dictionary contains a combined entry for 卯 and 夘 (2e3.1). Kojien simply cross-references 夘 to 卯, and the JIS Kanji Dictionary states that 卯 and 夘 are variants. I checked a Chinese character dictionary, and it agrees, showing 卯 and 夘 as having the same pronunciation (mǎo) and meaning. The only reference I can find that departs from the majority is the New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary, which has an entry for 夘 that I suspect is based on Morohashi.

And is 夘 ever actually used these days? Not much. You won't find it in Kojien or the big Kenkyusha dictionaries. To be frank, the Chinese zodiac is hardly a hot topic, and anyway the Japanese use 卯 instead of 夘 in terms such as 卯年 (うさぎどし: year of the rabbit). The 夘 kanji mainly appears in names such as 夘三 (うぞう), 夘一郎 (ういちろう), and 夘時 (ぼうじ). This name usage is probably why Japanese character standards include 夘. Note its readings in those names: う and ボウ; that's more evidence that the majority of dictionaries are on the right track when they align it with the same readings as 卯.

So what am I to put in Kanjidic for 夘? Do I go with Morohashi and regard it as a variant of 夗, or do I go with the majority and treat it as a variant of 卯? Well, in this case I think Morohashi got it wrong. Things may have been different back in the 1920s when he began working on his dictionary, but with 夗 vanishing from Japanese—if indeed it was ever actually used—and with modern scholars and those Japanese who actually use the kanji clearly treating it as another form of 卯, there is really no choice but to follow modern usage.

I didn't change the existing Kanjidic entry.