A Transfer to Heaven and Other Euphemisms

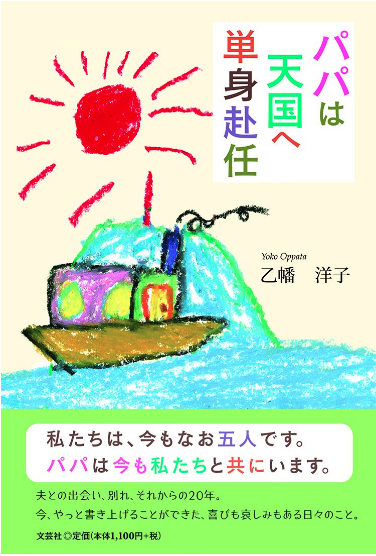

When I first saw this book cover, which I've included in the forthcoming essay 1751 on 赴 (to head to), I was astonished:

This term fills the leftmost column:

単身赴任者 (たんしんふにんしゃ: employee posted away from the family)

job transfer away from home (1st 4 kanji) + person

The title translates as follows:

「パパは天国へ単身赴任」

Papa's Job Transfer to Heaven

天国 (てんごく: heaven)

Daddy got a “job transfer” to heaven? That means he's dead! What a way to break the news to the kids! No, that won't screw them up at all or make them terrified of employment!

Lately, I have encountered several Japanese euphemisms, particularly in the new essay 1842 on 眠 (to sleep, rest). That makes sense, as humans prefer to think of death as a long, restful sleep.

The following sentence expresses that via 眠り (ねむり: (1) sleep; sleeping; (2) death):

死はよく眠りに例えられる。

Death is often likened to sleep.

死 (し: death); 例える (たとえる: to liken, shown here in its passive voice)

Although 眠り can mean "death," we're seeing it as "sleep" here.

Once again, 眠 is euphemistic in this term:

永眠 (えいみん: eternal sleep; death) ice + sleep

Death is an icy sleep! This term sounds formal, but people use it in pretty much any context. The following example reflects that the keyword can function as a する verb:

彼女は就寝中安らかに永眠した。

She passed away peacefully in her sleep.

彼女 (かのじょ: she); 就寝中 (しゅうしんちゅう:

while sleeping); 安らか (やすらか: restful)

The next term is completely synonymous with 永眠 and uses the same two kanji plus some additions:

永遠の眠り (えいえんのねむり: eternal slumber; death) eternity (1st 2 kanji) + sleep

Again, the Japanese use this word in almost any context, turning it into a verb with the addition of つく (就く):

永遠の眠りにつく (えいえんのねむりにつく: to die)

Here’s a way of using this euphemistic phrase:

義兄が昨日永遠の眠りにつきました。

My brother-in-law passed away yesterday.

義兄 (ぎけい: brother-in-law); 昨日 (きのう: yesterday)

We see another euphemism for death in this sign at a Tokyo cemetery:

Photo Credit: Lutlam

These terms appear in the first line:

50万 (ごじゅうまん: 500,000)

御霊 (みたま or ごりょう: spirit of a deceased person)

多磨霊園 (たまれいえん: cemetery name)

They surround this keyword:

眠る (ねむる: (1) to sleep; (2) die)

Although this verb can mean “to die,” the sign features it in the present tense, so “to sleep” is the rather sweet euphemism on display here. In other words, 500,000 spirits are sleeping at this cemetery. Shhh! Don't wake them!

The next line is as follows:

きれいな霊園に、ゴミの持ち帰りにご協力を!

To keep the cemetery clean, please cooperate by carrying home your trash.

きれい (clean); 霊園 (れいえん: cemetery); ゴミ (trash); 持ち帰り (もちかえり: carrying home); 協力 (きょうりょく: cooperation)

I'm amused to see ゴミ because I very recently met Haruna, a Japanese woman who once wanted to write a book about Westerners' wrongheaded kanji tattoo choices. She mentioned seeing 護美 on someone's arm and hearing the owner proudly explain that it meant "protecting beauty." Haruna told me that 護美 is the kanji rendering of a word we typically see as ゴミ. Either way, it means "garbage!" (One source says that the kanji rendering has been around since the 1960s, most likely.)

When you pick up garbage, you are in fact “protecting beauty,” Haruna reasoned, so she managed to stifle a snort and simply told the tattoo owner that “protecting beauty" is indeed the correct translation.

I don't think I could have done the same. Especially after hearing so many euphemisms, I feel an acute thirst for straight talk!

Here's a preview of essay 1842 on 眠:

Catch you back here next time!

❖❖❖

Did you like this post? Express your love by supporting Joy o' Kanji on Patreon:

Comments