Tracing Circles in Time, and in Japan

Last week, I went to three major social events in five days. That's highly unusual for a hermit who spends all day thinking about nothing but kanji and who generally likes it that way!

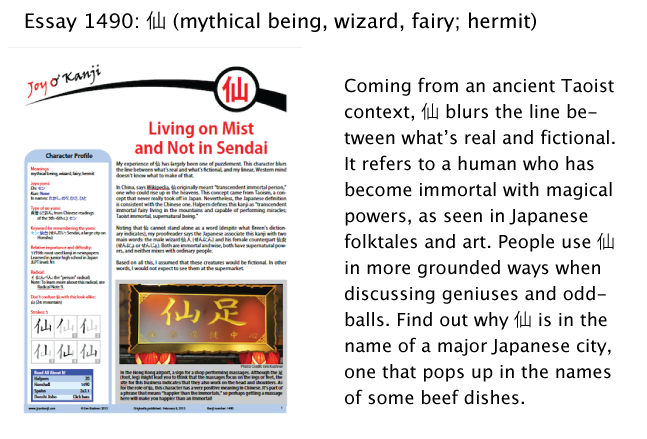

By the way, "hermit" is one meaning of 仙, the kanji of the week. Here's a preview of the new essay 1490:

Anyhow, these get-togethers gave me a multicultural immersion; I spent time with a Ghanaian on Friday, with dozens of Mexicans on Saturday, and with three Austrians (two of whom are kanji aficionados) on Tuesday. But rather than stimulating me to think about language and culture, these events made me acutely aware of the passage of time.

Saturday was a birthday party for a one-year-old boy. Nearly all the guests had young children, including a newborn, and these kids occupied our attention. They huddled around electronic toys that I couldn't hope to understand, getting along fine until one asked another politely, "Would you like to fight?"

Tuesday brought a birthday celebration for a 56-year-old. The guests spoke about knee pain and teeth that had fallen out, and nearly everyone peered at the Chinese restaurant menu through reading glasses.

But neither of these parties affected me as much the Friday get-together. For two hours, my college friend and I talked about things that happened 25 years ago, the people we knew, how we felt back then, and what has changed. I felt almost dizzy as I recalled college life and thought about who I was at that time—someone barely recognizable now. Back then, countless things made me feel alive and crazy and desperate and ecstatic and deeply wounded, sometimes all at once. None of those things matter in the least to me anymore.

My life has narrowed down to one focus—kanji. That's just about all there is! And it is more than enough. Writing Joy o' Kanji essays offers me the richest of explorations week after week, leaving me so fulfilled that I need little else.

How can I explain this to someone who hasn't fallen into the same addiction? I can't. As a result, there sometimes seems to be little to say to others, and it's hard to feel understood or known. Following a trail of kanji, or a million trails, I've ended up in an eerily beautiful alternative universe—maybe something as vast and mysterious as the Grand Canyon. I can't convey the experience to those who didn't accompany me on the journey.

Even if I hadn't had so much social contact lately, I might still be thinking about the passage of time, given the date. We've just passed through Setsubun (節分, せつぶん), which divides winter from spring in the traditional Japanese calendar. And this coming weekend brings the Chinese New Year.

By the way, when I wrote essay 1341 about 蛇 (snake) recently, I kept wondering to what degree the Japanese see the Year of the Whatever as a Japanese thing or as a Chinese thing. Obviously, it was originally Chinese. But do Japanese people see it as something that they have absorbed and made their own, as with so many other things? Also, do they view the Year of the Snake as starting on January 1 or more like now?

My proofreader filled me in: "The Year of the Animal thing applies to January 1 through December 31. And yes, we’ve made it our own. For instance, we make this joking remark:

彼はヘビ年だからしつこい。

He was born in the Year of the Snake, so he’s (as) persistent (as a snake).

彼 (かれ: he); ヘビ年 (へびどし); しつこい (persistent)

I had no idea snakes were persistent!

Although time marches on in a relentless, linear way, taking us from year to year with no return ticket, seasons turn time into a circle, which makes the experience of time more universal. After all, it is currently winter for everyone in the Northern Hemisphere, even if we're all at different stages of life. And perhaps the spinning of seasonal cycles makes the passage of time more acceptable. Every year we have a chance to return to something we left behind (for example, April) and to experience the same thrills as before when plum and cherry blossoms add color and scent to our lives.

With the seasons bringing us back to where we were, time is much like a snake with its tail in its mouth, forming a circle. I don't know why that image popped into my mind just now, but I've looked it up and found that the "Ouroboros" is a symbol associated with ancient Mediterranean cultures such as Egypt.

Nevertheless, there's a connection to Japan. Created in 1885, the woodblock print below shows an Ouroborous encircling an area of Japan. You can see a larger version here. Although the image is only partially displayed there, you can pull down the rest of the map. The diagram in the print explains the cyclical or Yin-Yang nature of earthquakes!

Yellow (a light beige, to my eye!) shows regions affected by a big earthquake on November 4, 1854. Blue indicates where a big tsunami subsequently hit the coast. And red marks the areas devastated by another quake on October 2, 1855.

The map is called じしんのべん. As you can see, though, ぢ志ん乃辨 appears on the right side. Here's the way to make sense of that:

ぢ would be written as じ today.

志 is an obsolete hiragana corresponding to し.

乃 is read as の.

辨 is an old version of 弁 and probably means "explanation" here.

Wikipedia says, "The Ouroboros could be interpreted as the Western equivalent of the Taoist Yin-Yang symbol." Aha! The new essay on 仙 includes quite a bit about Taoism (道教, どうきょう) and mentions its connection to yin and yang. Everything is circular, not just time!

Here's another bit of circular thinking. At the end of 2012, my proofreader mentioned that he would be attending an 打ち上げ会 (うちあげかい) at his workplace. I knew 打ち上げ as "launch" from when I had a launch party for Crazy for Kanji, so I wondered what he might have been launching. I looked up 打ち上げ会 and found these definitions:

打ち上げ会 (うちあげかい: closing party (e.g., a theater show); cast party; party to celebrate successful completion of a project)

So 打ち上げ can refer to both the beginning and end of something. That's hard to fathom.

The noun 打ち上げ comes from this verb:

打ち上げる (うちあげる: (1) to launch; shoot up; (2) (of waves) to wash up (ashore); (3) to finish (e.g., a theater run, sumo tournament); (4) to report (to one's boss, etc.))

Definitions 1 and 3 reflect the same contradictory meanings.

When it comes to the first definition, you can launch a rocket with 打ち上げる, which literally means "to fire upward." In this context, 打つ means "to launch," and 上げる means "to send something up."

As for the third type of 打ち上げる, the 打つ originally meant "to beat (a drum)," and 上げる meant "to finish." Together, they meant "to finish beating a drum." (A drumbeat has had a significant role in sumo tournaments and in theater productions.) This version of 打ち上げる later broadened to mean "to finish something that one has been doing for a long time." Now I see why it makes sense to have an 打ち上げ会 at year's end.

My proofreader notes that although the auxiliary verb -上げる (to finish) isn't commonly used today, it still shines through in verbs such as these:

書き上げる (かきあげる: to finish writing)

調べ上げる (しらべあげる: to investigate thoroughly)

切り上げる (きりあげる: to put something to an end)

勤め上げる (つとめあげる: to work for one organization until retirement)

育て上げる (そだてあげる: to rear a child until that child has become independent)

This -上げる is like the "up" in "to finish up," "to eat up," and "to use up."

Just one more thing before I close (up). The following term has to do with beginning something at the end of one's life:

晩婚 (ばんこん: late marriage)

As you probably know, 婚 means "marriage," as in 結婚 (けっこん: marriage). Because 晩 usually means "night," I thought it served as a beautiful metaphor in 晩婚. However, Halpern says 晩 means "late in life" in 晩婚 and in these words:

晩学 (ばんがく: late education)

晩年 (ばんねん: late in life), which appears in essay 2090 on 虹 (rainbow)

My proofreader says that the Chinese often use 晩 to mean "late." Come to think of it, English speakers have the same metaphor. We refer to our "twilight years." I suppose it's natural to equate the end of the day with the end of one's life.

Speaking of the end of life, it's not over till the old albatross sings. This week's news is that the oldest living wild bird has reproduced at age 62. Talk about beginning something at the end! This albatross is also known for having survived the tsunami generated by the 2011 earthquake in Japan. Everything circles around to Japan yet again! Of course! What else is there in life? Not much else, as I've discovered!

Have a great weekend!

Comments